Kestrels have big compound eyes that can see ultraviolet light, identifying the trail of urine from a mouse--all the better for the wire hawk to swoop down and come in for the kill. Insectivores, the purple martins have such good eyesight and agile flight patterns that they catch bugs in mid-air. They even drink water in flight, skimming the surface of a pond with their lower bills.

One after another, speakers came to the podium, informing us about bird habitat and behavior. It was the day of the annual Buggy Land purple martin seminar. The workshop hadn’t been held during the years of the pandemic, so we were happy to return to a place we knew well, plop down on a perch, and take in the surroundings.

Outside, our cars lined the gravel road in front of the Christian Aid Ministries Clothing Center, and across the way, horses and buggies were hitched up to the post next to the Sunday school house. The walls of the large CAM building were lined with racks of cardboard boxes filled with old clothes. A large table held doughnuts and coffee surrounded by young Amish men with displays of blue bird houses, lists of field trips, and instructions on how to attract your first martin scouts to your farm.

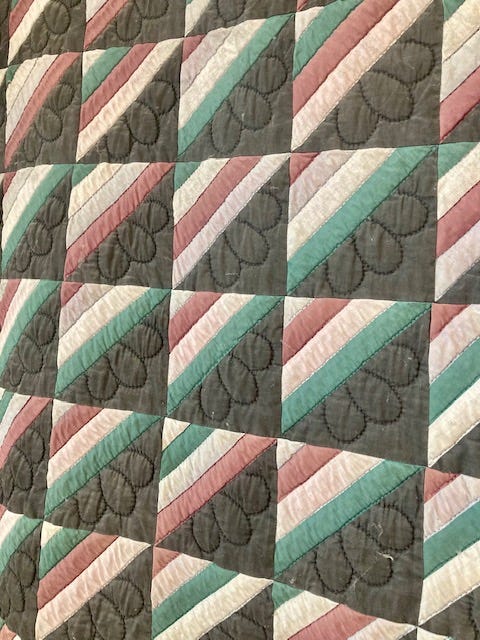

I only come to the Clothing Center once a year for the bird workshop. But I know I can find my neighbors here on holidays like New Year’s Day when we English sit around watching football games. Instead, the Amish share a meal and cut old dresses and slacks into squares to sew into quilts for the poor in international communities.

Late, the next speaker came running through the door into our community of bird lovers. Chris Jones, a research engineer, once worked for the university hydraulics lab until his blog about the destruction of our water quality became too popular. His book The Swine Republic did an excellent job of raising the public’s consciousness about our problems with pollution from industrial agricultural chemicals.

“Birds, you want birds?” Jones said. “Then you have to clean up the water. We have to change the way we’re farming.”

First, Jones spoke about habitat. In the early settlement days, when the Europeans arrived in the Americas, the Midwest was about 20 % wetland, 70% prairie, and 5% savanna. Now, most of the state of Iowa alone is privately held crop land.

“It’s too bad you cut down all the trees,” my East Coast friends say when they come to visit me here in my old Amish one-room schoolhouse. They assume that our landscape was identical to theirs, that there weren’t open expanses of land here, that all the space was taken up with forests. These remarks always remind me that we have landscape templates in our minds and geographical biases in our hearts.

But the Europeans who settled the Midwest were destructive. They cut plenty of timber in the upper regions of the country, but here on the central plains, they plowed up the prairie and they drained the wetlands. They viewed the prairie as a bunch of weeds, rather than an intricate ecosystem. They viewed the wetlands as mosquito breeding swamps, rather than homes for birds and other wildlife, and filters for dangerous pollutants.

“We don’t have a memory anymore of the rivers and streams before the arrival of the white settlers,” Jones said. “For we polluted the waterways as soon as we arrived.” We tiled the fields and straightened the streams, lowering the water table. We muddied the waters, changing the habitat for the fauna.

Most of all, after World War II, we introduced chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, the residue finding its way into the water and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico. Then, in the last fifty years, we supersized agriculture. We once had the land feeding our livestock and the livestock, in turn, fertilizing our land, and feeding us. After the Farm Crisis of the 1980s, we began raising animals confined inside sheds in CAFOs, or confined animal feeding operations. We plowed up even more land for the push to grow more corn for ethanol.

Soil erosion increased and the nitrogen from fertilizer and CAFO waste fouled the already polluted waterways. Lakes and ponds became too filthy to support recreation or the same level of bird life. Private wells were contaminated by nitrates, causing health problems, the rates of cancer rising. Much of the burden of this pollution fell on the shoulders of rural people who couldn’t bear the expense of clean-up. Right now, we have a million people drinking contaminated water in the state. A third of the population.

“So what do we do?” Chris Jones asked, “First, we need to address ethanol.”

I looked out over the heads of the audience. My neighbors agreed. They weren’t thrilled about ethanol. You can’t feed ethanol to a horse. “And why should I burn my grain?” the Amish often ask me.

“Why do we use CAFOs? They’re efficient and run on cheap fossil fuels.” Jones said.

The Amish use fossil fuels sparingly.

“There are alternatives out there.”

Yes, that’s right. There are alternatives.

“Both the Republicans and the Democrats support ethanol and Big Ag. It isn’t just one side or the other.”

The audience stared back at Jones.

“Political candidates campaign here, promoting ethanol.”

The Amish don’t vote. . .

“We need to change government policy.”

. . and are discouraged from getting involved in politics.

“We need land reform.”

The Amish don’t sue.

“We need better regulations.”

“Regulations” aren’t a conversation starter in Buggy Land.

“We need to buffer streams, ban fall tillage, ban spreading manure on frozen ground, stop applying too much nitrogen. We need more public land.”

The audience nodded.

We need more diverse farming, more four crop rotations,” Jones said. “With livestock back on the land.”

Silence filled the room. The smell of chili simmering on the stove in the lunch room drifted toward us.

Finally, a man raised his hand. “That’s what we’re doing here,” he said. “In farming organically.”

Another man spoke up. “Right here in this area. We have the highest concentration of organic farmers in the whole country.”

Jones nodded.

I pulled back my perspective, as if I were peering down at this dynamic from a treetop. Maybe the growing organic and regenerative agriculture movement could gain enough momentum to turn around the food system. We certainly have a good start here. Most of the Amish in this area see the value of in this endeavor. But the power structure doesn’t. And is there enough incentive for English farmers to reach a critical mass? Before our water gets even worse? Before the birds have disappeared? That would take policy change and a new vision.

After lunch, I drove home, my humble human eyes scanning the brown fields and overcast skies for signs of spring: the Canada geese flying above, the red-winged blackbird perched on the fence post, the kestrel boxes ready to be occupied, and on almost every farm, purple martin houses on their poles waiting for the return of their mating pairs to take up their places in the colony. Soon, the days will grow longer, the soil will warm. Soon, the martins will dive down, sipping the pond water on the wing.

Find out more about Mary Swander on her website: www.maryswander.com

I am thrilled to be part of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. We will be having our monthly Zoom chat on Friday, March 29, 2024, at noon CDT. Join us with this link:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87372900028#success

Or, check us out in our Sunday Round-Up:

It seems like Chris Jones was preaching to the choir. It encourages me that there is a choir; I only wish it were larger.

This post had/has me on the edge of my seat, heart in my throat. Thanks for sharing the land where you live, Mary, where there is "a good start." What will our kind choose? Can we learn to see more clearly, widely and wisely?