“Together, the two drowned men left seven children in this school,” the elementary school principal told me. “And all the other children, of course, are cousins and relatives. One day they are doing really good, then the next, they slump down in their desks. ”

On the bulletin board in the school, just inside the main door, the principal had hand written a sign in big, bold, black letters: SWIMMING LESSONS BEGIN APRIL 30.

The preparations for the funeral began in Claddaghduff on April 24. First, the fishermen’s currach was burned. No one would use a boat that had caused the death of others. A currach is a traditional Irish canoe, fashioned from an intricately designed wooden slatted frame. In the past, animal skins were stretched over the slats, but now canvas is used as a covering.

Once the canvas is in place, the whole boat is waterproofed with several layers of tar. The currach design uses little precious wood in this treeless landscape, and has had a long seafaring history. St. Columba is said to have used a currach, and in the sixth century St. Brendan may have made the first translantic voyage to the Americas in a currach.

Currachs are tipsy. But the small, light boat was said to navigate the rough seas better than a larger vessel. And in a poverty-stricken land where well into the twentieth century, the roads were cow paths, a small, handmade vessel was often the best option for transportation.

The news of the autopsies drifted onto the Claddaughduff shore. One man was drowned outright, the other had a blow to his head that knocked him unconscious before he went down. Their bodies were embalmed, then taken back to their homes—just yards from each other—for the wakes. Thirty men went to St. Brendan’s cemetery on Omey Island and dug two graves—one for the older man in the older part of the cemetery, the other for the younger man in the new addition to the graveyard.

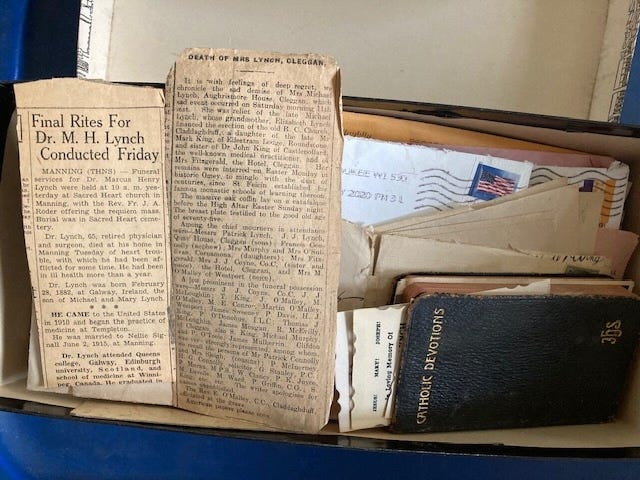

Early Thursday evening I watched people stream in and out of the dead men’s houses for the wake. The visitors, dressed in black, often carried sympathy cards or dishes of food. I knew the scene well from all the wakes I’d attended of my mother’s relatives. First, before the body and the visitors arrived, there was a mad effort to clean up the house. The women in the family yanked themselves out of their grief to tie rags around the end of the brooms, knocking cobwebs from the ceiling with fierce, sweeping motions of their arms. They scrubbed down the bathroom, then gathered together every bit of clutter—newspapers, magazines, mail—and threw it all into a big box in the closet just in time for the hearse to pull into the drive.

Car doors swung open, slammed shut. Men emitted short, breathy groans, their biceps straining, carrying the casket up the front steps. Furniture was rearranged—the sofa shoved to the far end of the room-- to accommodate the casket. Clean, dressier clothes were pulled from the closet, good shoes wiped of dust, combs run through hair.

The next-door neighbors were the first to arrive with biscuits and cakes. They headed to the kitchen, the women orchestrating the refreshments, brewing tea, arranging cups, saucers, napkins, and silverware. Men began to pool outside on the front steps. More visitors streamed up the walk, heading straight into the living room. I’m sorry. I’m very sorry. They took the hands of the widow. Then turned to the deceased, rosary beads wound through his hands. They stared down at the fisherman—brother, cousin, friend, neighbor-- uttering a prayer. Holy Mary, Mother of God. . .

More and more mourners poured through the door. They moved back and forth between the two houses, paying their respects first to one family, then the other. The houses filled with dark clothes, with sobs and handkerchiefs. The houses filled with sandwiches half-eaten on plates. The houses filled with the rattling of tea cups, with the story about the deceased, a happy memory whose telling moved from neighbor to neighbor, each contributing part of the plot. The noise in the room swelled, then burst into laughter, laughter that shattered the air that held a faint smell of formaldehyde.

The next morning, the early air was damp and misty. I opened the front door of the cottage and my bicyle rested against the stoop, the tire fixed. Through the lens of a pair of binoculars, I could see waves lapping at the Inishbofin Island shoreline, spraying bits of foam into the air. The early ferry sped across the water toward Cleggan harbor and the Pier Bar where several smaller craft were docked, their red bows bobbing in the water. Several dozen lobster pots were stacked high on the pier, blue marine lines woven through the wire mesh.

Around eleven o’clock, Happy the dog plopped down on the floor beside me. The sun came out and the day turned bright and clear. We sat at the dining room table again, and watched the traffic on the road. First, one vanload of people, then another, a car filled with five or six family members, then the first hearse. Then the second sped by. The funeral was scheduled for noon when the sea was at low tide, the water receded enough to open the strand to Omey Island.

Just before noon, Happy and I hiked up the hill to Claddaghduff. From the stone wall overlooking the ocean, I glanced down at the Catholic Church just on the edge of the sea. My family had donated the land and helped build Our Lady Star of the Sea. Now families from all over the country of Ireland were pressing inside. Two rows of well-worn pews flanked either side of the nave with the altar taking center stage in the chancel. With trees scarce in this part of Connemara, the pews and the curved ceiling beams were carved of driftwood. The sun poured through the stained glass windows recessed into the walls, illuminating simple, bold likenesses of St. Patrick and St. Brigid.

Five priests awaited the caskets that were carried the short block from their homes. And over five hundred people, unable to squeeze inside, milled around the churchyard. They stood there waiting to hear the funeral mass through the opened windows and doors. Fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, husbands and wives, dressed in sports coats, and skirts.

It was the biggest funeral ever in Connemara, the villagers told me, but the numbers were a bit of a misrepresentation. Many Dubliners had read Feichin Mulkerrin’s obituary, then jumped in their cars, driving to Claddaghduff for the funeral. The Dubliners had no idea that the village boasts at least three Feichin Mulkerrins. The Dubliners were shocked when they gazed into the church and found their Feichin alive and well sitting in one of the pews.

Whether in attendance for the proper Feichin or not, the mourners all remained in place for the funeral that lasted nearly an hour and a half. At 1:15 P.M. about thirty people seeped off of Omey Island, slowly edging their way across the strand toward the church. At 1:30 the pallbearers carried the caskets out of the church and into the two black hearses. The immediate families of about fifty people followed behind, winding their way down the narrow pathway toward the strand, open and clear of water for several miles in each direction. Hundreds of people followed the families, most on foot, some in cars and motorbikes. The sky had turned aqua with big foamy cumulus clouds hanging on the horizon.

Then the funeral procession moved out through the parted sea, a procession emblematic of processions that have been repeating themselves here in this place for centuries, processions that carried the bodies of the young and the old, of those who had come home prepared to die, of those whose had called this home all their lives but had been unprepared.

I keep the obituary of my great-grandmother Mary King Lynch in a shoebox on a shelf at home in Iowa. Born into the Great Famine, she lived to old age here on this peninsula. The funeral mass was said in Our Lady Star of the Sea, the newspaper clipping said, then the body was carried across the strand to the family plot on historic Omey Island. Now I was watching a recreation of my great-grandmother’s funeral, and all the family funerals that had embarked for over a century from Our Lady Star of the Sea Church.

The black hearses moved across the strand, slowly, inching forward. The Omey Island inhabitants—just a couple of people-- met the procession and fell in line behind them. Soon, the procession stretched the length of the strand, at least a mile and half, the mourners little black dots against the white sand. Inside the hearses, the caskets were covered with flowers—roses and carnations-- the one splash of color in the black and white scene.

One stride, then another, the families took direct, steady steps, all staying in sync, leading the other mourners in a rhythmic slow march, a silent meditation on the lives of their loved ones, of the dangers of the sea that has provided an unreliable but necessary income, a sure but perilous means of transportation, a magnificent but wild backdrop to their existence. What is it like to live with the history of so many accidents, so many loved ones lost to the sea?

All who live in this western tip of Ireland know the anxiety of trying to eek out a living on this landscape, of rocks, bogs, and sea. All know the stark beauty of this place, but also the shadowy undertow. The word Claddaghduff, after all, means dark shore. How does one live in opposition to such a threat? How does one engage in life with hope in the face of such peril? How many centuries have these people, my people, walked across this strand carrying this burden in a box.

The procession trailed up the hillside into the newer part of St. Brendan’s cemetery. They let the ropes of the younger fisherman’s coffin down into the shallow grave, the priest reciting the burial rite, the mourners, buoys, around the grave. The male relatives of the fisherman each took a turn with the shovel, dropping chunks of dirt onto the casket, one scoop and then another. Ker-plunk. After the relatives, the fisherman’s neighbors took up the tasks. Ker-punk. And after the neighbors, friends. When the grave was filled over with dirt, chunks of sod were placed over the four-foot high mound. Bouquets of flowers were laid on top of the sod, then a fishing net was cast over the whole burial site, holding down the flowers and sod from the fierce wind.

Slowly, the procession moved to the older part of St. Brendan’s, past the O’Toole plot with the tiny replica of a currach and lobster traps encased in Plexiglas, to a family plot very near our family’s gravesite. This part of St Brendan’s was marked with family names. Lacy, Feeney, Lynch. Here, the older fisherman was buried near his mother and brother. Ker-plunk. The priest’s prayers rose into the air, the mourners murmuring the responses. The dirt filled the hole. The sod covered the casket. The flowers covered the sod. And the net, the net trapped all.

The crowd made their way back across the strand—the empty hearses followed by the bereaved families. Cars and motorbikes zigzagged around the procession to reach the mainland ahead of those on foot. And when the last had come ashore, the families returned to their houses, the visitors to their cars, and the villagers to the pub. Slowly, the tide began to rise, lapping at the edge of the strand, then little by little making a gradual slide over the strip of land, the thin filament that anchored one island to another. The sky held onto its blue radiance and the sea rose higher, matching the hue. On the horizon, sky and sea became one, St. Brendan’s cemetery adrift in the Atlantic Ocean. The water rose even higher, the strand completely covered, and Omey Island was an island again.

This essay was originally published in a slightly different form in Thinking Continental: Writing the Planet One Place at a Time, by Susan Naramore Maher, Tom Lynch, et al.

Come and enjoy all the columns of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. Follow us on Wednesdays for the Flipside and on Sunday for the Round-Up. Best paper in the state.

Your writing is so powerful, Mary. I was with you on this journey as well. The Irish reaction to death in this instance is the same one I grew up with. The wake is full of sadness and laughter. It is how the Irish weave life.

Oh so heart wrenching and dramatic. I cannot begin to imagine a life like that.