The Amish have continued gathering around Bertha’s deathbed, each neighboring household rotating throughout the week to the Yutzy’s farm to open their hymnals, sing in harmony, and create an atmosphere of deep connection to the Divine. The families have arrived in identical buggies, the men dressed in dark pants and suspenders, the women in black bonnets. But each family, with their unique vocal cords, creates a distinct sound, the notes drifting toward me over the slope, the volume fluctuating with the wind, the rain, and the mist.

At the same time, inside my house, I watched another ritual, this one a broadcast from The Irish Times. So similar but so different from the Amish. This time, through the wonders of the internet, I was experiencing an island culture off the west coast of Ireland. In 1890, thirteen skulls had been stolen from Inishbofin Island—a tiny community of 170 where some of my relatives still live. Two British anthropologists, Alfred Cort Haddon and Andrew Francis Dixon, had been taken up with the then-popular study of craniometry and anthropometry, comparative scientific measurements of human characteristics.

Under the pretense of a fishing survey, the two anthropologists landed on Inishbofin and stole the skulls from a recess in the wall of Teampall Chaomháin adjacent to an ancient monastery. Local history then reports that in the dead of the night, the men snatched the skulls off the island in a sack, claiming they were transporting moonshine whiskey, or portīn. “When the coast was clear, Haddon said, “we put our spoils in the sack, and cautiously made our way back to the road, then it did not matter who saw us.” They took the skulls to Trinity College in Dublin to be probed, measured, and stored away from public view until now.

The islanders might be able to forgive and forget the theft of potín, but not the theft of their ancestors’ bones.

“It’s a full stop at the end of a sentence,” Marie Coyne told the Times reporter. Coyne, a photographer and director of the local museum, lead the Islanders’ campaign to reclaim their ancestors' skulls. It had taken years to get the final permission to go to Dublin, drive the skulls in a traditional wooden coffin made by islander Christopher Day across the country, carry them onto the ferry, unload them on the pier, then embark for a funeral Mass in St. Colman’s Church on Inishbofin.

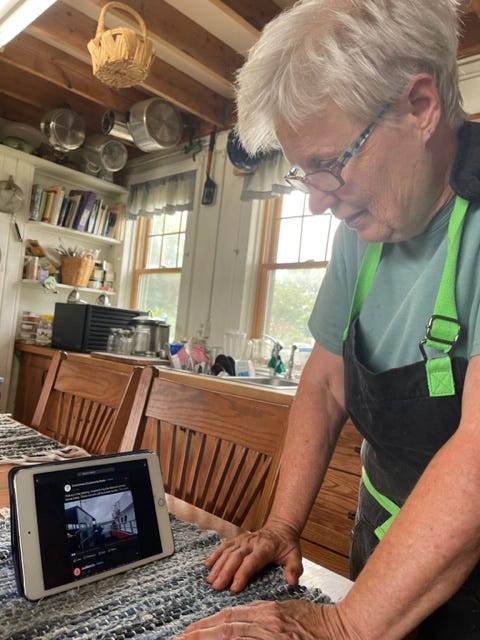

I peered at my iPad, watching shots of the coffin resting alone inside the ferry, a boat I knew well. Many times, I’d squeezed into one of the seats with a crowd of teachers off to a week-long ecological field course on the island. We’d hiked around the spectacular geographical features, the bogs, lakes, stags, and blow hole, then the ancient ruins of Cromwell’s castle that once served as a prison for Catholic priests, and the monastery, a site dating back to 14th century. We laughed, sang, and danced in response to our adventures. I lead workshops in creative writing that incorporated our experiences.

In contrast, it was a sober and profound experience to watch the four pallbearers carry the wooden coffin on their shoulders up the steep and winding Low Road to the church. Marie Coyne led the procession, and when she tired, another islander slipped into her place. So, the community took turns with their precious cargo, rotating in and out, and sharing both the burden and peace of mind of their task.

At the church, a structure that looks so like the Irish-Catholic churches of my childhood in Iowa, Haddon’s granddaughter stood at the pulpit during the funeral Mass and offered an apology for the theft, an ironic statement from the descendant of a man known beyond Inishbofin for his opposition to racism and colonialism.

On the way to the gravesite, the procession passed meadows of tall grasses, grasses the islanders refused to mow to protect the ground-dwelling corncrake. The threatened bird, once common over much of Ireland, began to dwindle with the rise of agricultural mechanization and implements that swept through grasslands and fields of grain. Inishbofin has become a refuge for the corncrake, or landrail, the bird feeding on grain seed, singing with its distinct call, and migrating in the winter to Africa.

At the graveside, islanders had hand-dug the grave, several feet down into the ground, land I’d walked so many times on the ecology course, my feet slip-sliding on the rocks, my eyes scanning the Celtic crosses and markers for the names of my relatives. At their conclusion, dressed in slickers and work boots, a rainy mist in the air, the men leaned against their shovels, their collie dog peering into the hole, a pile of dirt at her side.

The coffin was eased into the ground with keener Caitríona Ní Cheannabháin and musician Eoin Mac Casarlaigh, singing a lament, a vocalization of grief, support, and comfort. The singing filled my kitchen, so like the singing I had been hearing outside my door. My Amish neighbors' hymn floated over the field, the chorus embracing a return to their heavenly home. The Irish tune carried a haunting chant, a background rhythm that was both sorrowful and driving, seeming to say, We have to get through this. We have a task on hand.

Ker-plunk. Shovels lifted clumps of dirt, covering the wooden casket in the newer part of St. Colman’s cemetery. The islanders patted down the soil on the sacred site that was intended to be a refuge for their threatened relatives, a return to safety. At that moment the grave became symbolic of all humans, species, land and artifacts taken from their homes, demanding return, repatriation. Then the islanders placed white stones on top of the grave with a marker that read:

Here lies the remains of our ancestors

including 13 skulls.

Removed without permission from

St. Colman’s Monastery,

July 16, 1890.

Held in Trinity College Dublin

for 133 years.

Returned for burial,

16 July, 2023.

Listen to my latest podcast “I Do” from Mary Swander’s Buggy Land. I am pleased to be part of the Iowa Podcasters’ Collaborative.

Iowa Podcasters' Collaborative

Please support my colleagues at the Iowa Writers Collaborative:

Very touching Mary. Thank you for sharing.

Such a moving story and juxtaposition and who better to tell it and bear witness.