Spirits

My parents were draft dodgers. My father stayed in the Navy Reserve after serving in the South Pacific in World War II. Upon his release, my parents married, lived near Chicago, and had two small boys. Then the Korean War broke out and my father’s unit was getting called up. My mother was pregnant with me and couldn’t bare the thought of widowhood with three children to raise alone.

“So what can we do?” my father asked.

“Move,” my mother said.

“To where?” My father had a job in Chicago and they lived in a rented basement of a summer cottage on the Indiana Dunes. In the post-war economy, jobs weren’t easy to find, and housing was even more difficult to locate.

“We’ll go back to Manning and move in with my folks,” my mother suggested. “And you’ll drive to Omaha and look for a job.”

Soon, they were on the run to western Iowa where the population was sparse, and the call for reservists low. Western Iowa had provided cover for the likes of Jessie James, Bonnie and Clyde, and John Dillinger. Why not the Swander gang?

They moved into a large Victorian house in Manning (population 1500) that my grandmother had bought during the Depression for $1,000. My grandfather had just passed away, so my grandmother lived in town and ran the family farm from there with a tenant on the “home place.”

My grandmother lived downstairs in the Victorian, and my parents fixed up the upstairs as our living quarters. The place needed some repair, so my parents painted, refinished floors, and replastered. Then my father turned to rewiring, installing lights with dimmer switches and even an intercom so the “upstairs” could talk to the “downstairs.” This innovation, of course, was rarely used as my grandmother preferred to just bang on the hot water pipes with a metal spoon when she wanted our attention.

But the rewiring did yield big rewards. One day, my father discovered a jug of Templeton Rye stuffed down between a wall and the studs. Templeton Rye was the American poitín, or bootleg whiskey, made in a village by the same name near Manning. German Catholics in Templeton--with a few Irish mixed in—began experimenting with rye mash as soon as prohibition laws swept the land.

Carroll County was a center of German Catholic immigration in Iowa. They brought their Old World traditions to the open prairies. Unlike their Protestant neighbors who were dry or frequented dark saloons, the German Catholics drank beer and other spirits at family celebrations and festivities. A wedding wouldn’t be a wedding without a keg and beer steins. The local Irish Catholics joined in the fun, with a taste for whiskey on their tongues.

A few farmers ran the mash through copper coils, then Thy will be done, they had a beverage for the whole family. Eventually, the family became the town, and the town became the region. The whiskey was brewed in small batches in both the countryside and in the village, in barns, garages, and sheds. The basement of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church pumped out whiskey every day that went into barrels shipped by trains to Omaha, Kansas City and Chicago. Soon, the story goes, Templeton Rye became a favorite of Al Capone, and trucks ran the blessed liquid to Chicago every day with shotguns strapped to their running boards.

A federal Prohibition agent named Benjamin Franklin Wilson was put on the case but he had a hard time catching Joe Irlbeck, the kingpin of the illegal hooch. In the Depression, bootleg liquor brought a much better price than most anything else a farmer could produce, and Irlbeck had a 40-man payroll, producing 1000 barrels a day.

Wilson and Irlbeck tipped their hats to one another on the street. Everyone in Templeton was in on the scheme, and no one was about to squeal. The hardware store ordered the copper tubing that was bent into coils. The shopkeepers kept bottles of the whiskey hidden behind counters for clandestine sales. The undertaker stashed jugs of Templeton Rye in empty coffins. The farmers used their hogs to roll the whiskey barrels around their barns to speed up the fermentation process.

On the occasions when Wilson did catch up with the bootleggers and brought them to trial, the juries usually let them off, and Hail Mary, full of grace, the operation started back up again. In 1931, some Iowans were outraged when they picked up the Des Moines Register and saw a photograph of a cutout of a little brown jug with the words XMAS SPIRITS strung up on a garland swinging across the main street of Templeton.

Boy, do they have nerve!

Now, they’re advertising, right out there where everyone can see it.

And on Christmas!

The bootlegging went on well past the end of Prohibition when Joe Irlbeck finally cut a deal with Wilson and bought a bar in the nearby town of Dedham where he sold legal liquor. But Holy Mary, mother of God, a “value-added” product like Templeton Rye still brought in good extra income. Then as the economy improved with the war, the hooch became more and more scarce.

Things were quiet in Templeton until the mid-1970s. I was back in the old Victorian house, sorting through the family belongings, my grandmother and mother both having died in rapid succession.

“They’re at it again,” one of my neighbors told me. “In Templeton.”

“How are they getting away with it now?” I asked.

“You ask your barber for a bottle, then he asks the butcher, then he asks the feed and seed dealer until it gets to the source. Then the bottle comes back down the line, one by one, and no one really knows where it ends, or who is brewing the stuff.”

“Clever.”

That summer, I sat under a single light bulb hanging down from the ceiling of the attic, sweat pouring down my forehead, going through old family photographs, letters, and ledgers. I found pictures of my ancestors I’d never met, the resemblances commanding and clear. I found addressess of relatives on the East Coast, those who had made the voyage to the States with my grandfather but had remained in New York in the tenement buildings. I found the letter of blessing that my great-grandmother had written from Claddaghduff to my grandfather on the day of his wedding.

And my grandmother’s records from the Depression were fascinating, documenting her attempt to keep the farm going through one of the worst economic periods in American history. She recorded her expenses and income, when she sold her crops, when she sold her hogs. Slowly, over the course of the Depression, she was making a profit, not a huge profit, but more money than I expected for those times. She was hanging on to the farm despite the low prices. What a lot of hard work. What a good manager, I thought. I read through page after page.

Finally, I got to 1936. After the usual debits and credits, my grandmother had drawn a hard pencil line across the page, the lead at once thick, angry and resigned. There were no calculations beneath the line, no numbers, no totals, no balances. Just a blank space and these words in her hand writing:

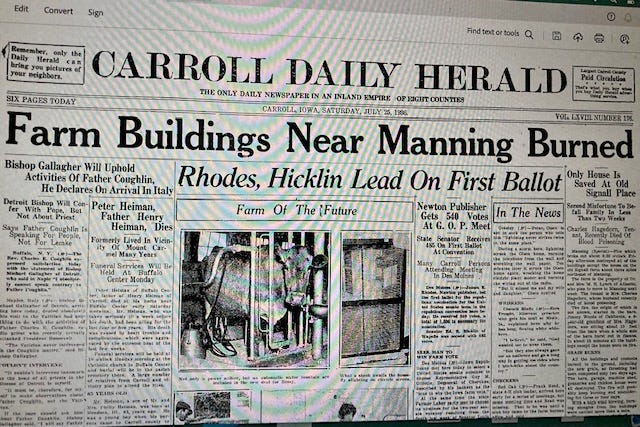

Still blew up in barn and burned down all buildings on home place.

Mary Swander is the author of numerous books of poetry, non-fiction and drama. She has won many national awards, the latest the Anon was a Woman Environmental Art Award (New York Foundation for the Arts) for her new play Squatters on Red Earth. To read more of her work or bring this drama to your community, contact her through her website: maryswander.com

I am pleased to be in cahoots with the members of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. Check us out through our IWC Sunday Round-Up:

Cousin Mary

For better or for worse- alcohol has a strong part in our family histories. Our Grandfathers were brothers and for me this was the paternal side of the family. The interesting prohibition story from my ancestry comes from the Maternal side of the family where my grandfather was a prosperous owner of several taverns in Jersey City, NJ when prohibition struck. Ever resourceful, he kept the taverns open as eateries. Most of the alcohol was kept in his home and the legeend is that it was kept under his children’s beds. His brother in law, a Jersey City police captain steered him whenever the Feds were coming to inspect and

What an amazing story, Mary!