Patches

Patches

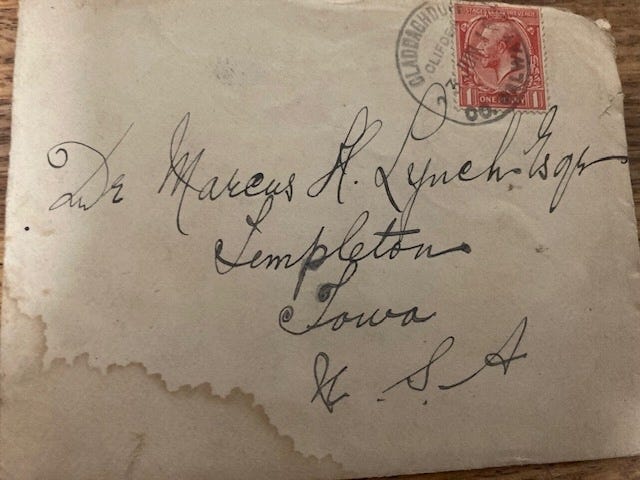

Claddaduff

Clifden

Co. Galway

June 22/1915

Dear Son & Daughter,

I am sending you my best congratulations, also my blessings & was more than delighted to hear from you.

I placed my right foot on the middle rung of the metal gate, then swung my left leg up. I threw my body weight over the top of the gate and into the pasture surrounding my Irish heritage homestead. This was where my grandfather grew up, where he departed for Queens College in Galway, then to Edinburgh to study medicine, all financed by a wealthy uncle. When that money ran out, it was on to Winnipeg, Canada, and finally to finish his studies at the nearest medical school— in Des Moines, Iowa.

And here I was from Iowa, at long last, making contact with this historical part of myself, striving for that elusive connection between the living and the dead.

Once on the other side of the gate, I found the padlock and chain easy to disengage. My friend and guide Bernadette entered. Mud oozed around my Wellingtons, my feet taking short strides along the path to the cottage. And there it was, hidden away on a slight rise in the land, a small house made of stones piled on a landscape of stone. The cottage was far away from the road, almost in the sea. Bernadette told me that cottages were placed strategically, usually on a rocky spot, to prevent them from spoiling any tillable land.

How different from land use at home, I thought. In the States, we love to build houses as big as ships, surrounded by vast expanses of lawn. Then we spend much of our weekends sitting on small tractors sailing round and round, mowing these non-productive oceans of green.

Here, the ocean lapped at the shore, the sand stretching across the strand to Omey Island and St. Brendan’s, its ancient sacred cemetery. The gravestone of the Lynch family poked up toward the blue sky, the coffins, one stacked on top of another, sinking into the sea. Here in this cottage with its view of Omey Island, my Lynch ancestors were forever reminded of mortality, of their final resting place. St. Brendan’s Cemetery was always straight ahead in their vision, an omnipresent fixture in their daily lives.

I am sorry my dear Mark your sister Delia Maria is in very poor health at present but I trust in God she will get well & that we will all have the pleasure of meeting again. When your letter reached us we all thought if you were here you would be able to do something.

I stepped into the dark kitchen of the cottage, the one room that was still mostly intact. The door was gone, but the boards of the frame were still there, painted bright red. I smiled at the thought that there had once been a bright red door on the cottage. I recalled the story of Queen Victoria’s husband’s death in 1861. Overcome with grief, his widow commanded all her subjects to paint their doors black in mourning. In rebellion, the Irish painted their doors red, blue, purple, yellow, and green—every bright color—but black.

What other drama, what dailiness took place in these rooms of this small cottage? The walls were traditionally crafted from stone wedged against stone, large, heavy rocks piled on top of one another with smaller chinks filling in the gaps. No mortar was used on the outside. Inside, the dense walls were plastered and designed to protect from the lashing winds and gales, absorbing the heat from the turf fire in the hearth in the winter.

The main room may have once had a fireplace and hearth on one side, but there was little evidence of a chimney anymore. In some cases, the chimney rose up toward the ceiling, then wafted its smoke out through a hole in the wall. The 1911 census reported that the house had six rooms and four windows with the widow Mary Anne Lynch as head of the household. Four grown children and two grandchildren were still living in the house. The homestead included several outbuildings including: a chicken coop, stable and coach house, a “piggery,” a barn and potato house.

Now the roof was a piece of corrugated metal. According to the census, it may have once been slate or iron. All the surrounding cottages had thatched roofs that cost less money but took more maintenance. Every year, a thick layer of straw was laid over the last one until the underlayers rotted. Then, on an average of every 10 years, the whole roof was stripped and replaced, the rotting straw used for animal bedding.

There were no windows in the main room. In the old days, the more windows a house had, the more rent the tenant had to pay to the landlord. So in a typical cottage, the doors were cut in half. The upper half of the door could be opened for light and circulation. The lower half could be kept closed to keep toddlers in and chickens and pigs out.

The floors were mostly clay. Boards were sometimes used in the bedroom, but in a treeless landscape, wood was scarce. Furniture: a few stools and a small table carved out of driftwood, a small dresser pressed against the wall that held some earthenware plates and cups. A quilting frame.

The Lynch cottage bedrooms had long since caved in. It looked as if there had once been a loft for storing grain. The smaller rooms had once held several beds and perhaps a few chairs. A spinning wheel. Now weeds and brambles grew up around the stones.

Sadie is married and living in Cleggan. She was delighted to hear you were married and settled down.

There once were ten children in the Lynch family, 12 people living in this small house. They all spoke both Irish and English. They all knew how to read and write. How in the world did they all squeeze in here? They must have had to live outside most of the time. Thank God, they had shoes.

I imagine my great-grandmother sitting at a small table on a wooden stool in the kitchen, a picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus hanging on the wall. Potato soup cooking in a kettle over the fire. She is writing to her son in English. He lives on the prairie in Iowa and has just gotten married. Iowa, wherever that was . . .

Perhaps you could come home on a trip soon. We will all be glad to see you if you come. Don’t forget to send me your wedding cards.

“Our ancestors thought America was the next island,” one of my Irish cousins had once explained. “They didn’t know how far away it was.”

The night before a son or daughter’s departure, family and friends would gather together for an American wake, a night of drinking, dancing and mourning the loss of a loved one, as if the emigrant were a corpse. The next morning, the young person stepped on the boat with just a few belongings, never knowing if or when they would return.

Francis is home from America himself with wife & child, having a splendid home beyond Clifden. You remember where the races used to be near Clifden.

“So, mothers would send off their sons and daughters with a little sandwich wrapped in paper.”

Write soon and send us a big long letter to tell me all about yourself.

But emigration was an escape hatch, a way to survive, and one less mouth to feed in a small house filled with younger children.

Since you left home now, you must be a kind husband & I give you my blessing.

My grandfather was never able to make it back to Ireland. He never saw this cottage nor his mother again. He never had a chance to introduce his wife or his baby daughter to his family.

If you be otherwise, I will be displeased with you.

But here, a hundred years later, was a homecoming. I hoped that the spirit of my great-grandmother and the spirits of Omey Island, the spirits that dwelt among these ruins, these beautiful granite stones, that fit so tightly together, were pleased.

Your fond loving mother,

Mary A. Lynch

Become a paid subscriber and join the Iowa Writers Collaborative for our Office Lounge chat on Friday, August 30 at noon CDT. I’ll send the Zoom link to paid subscribers on Friday morning.

Please check out and sample writing from the collaborative through our Sunday Round-Up.

How lucky you were to find the cottage still present, even if in ruins. I think of how my grandparents’ beautiful farmhouse in Greene County is long gone; nothing remains of the buildings they built and made memories in. The physicality of your ancestors’ home truly resonates in a way a patch of land with new buildings will not.

I love it!!! Good on you. You made it happen. stay away from Bush Mills, they are protestant......😉