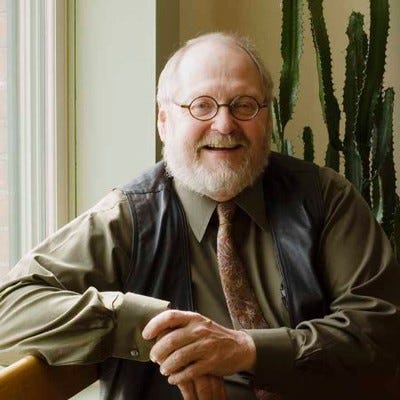

In answer to my column about home butchering, I received an outpouring of stories about procuring and processing meat and fish. With the Ukrainian war dragging on, and all of us reckoning with its destruction, this story by Dr. Eugene Zdrazil, a chiropractor near Lone Tree, IA, caught my attention.

Seventy years ago, seven-year-old Gene Zdrazil sat in the backseat of his grandfather’s car, rattling across a rickety wooden bridge carrying him onto the thick, shimmering ice of a northern Minnesota lake. This was one of Gene’s first ice fishing expeditions and he was overwhelmed by the live, breathing, creaking, groaning ice. His grandfather kept the car windows open for fear that they would fall through the ice, the water compression trapping them inside the car. Gene worried that he wasn’t dressed warm enough and his grandfather—a gruff, scary man– an immigrant from Bohemia—reassured him they would soon be in a tiny house with a kerosene heater.

My grandpa, Joseph, was frightening, really. He taught me to swear, for instance, instead of cry. My mother wasn’t thrilled with that, I can tell you.

So, Gene didn’t cry when he stepped out on the ice where they met Gene’s grandfather’s friend Otto there in the late afternoon at ten below zero. Instead, Gene marveled at the night sky.

Low and behold, I look up at the sky, and I don’t know if it was because I had a seizure disorder or what, but I couldn’t stop looking at the stars. It looked like you could reach them and pluck them out of the sky. I’d never seen that many stars seemingly that close.

Soon, Joseph’s arm stretched out of the ice house, pulling Gene away from his revery. Inside the shanty, Gene was determined to show his own pluck. Around and around, Gene chiseled the hole through the two and half foot layer of ice, one end of a leather strap tied around his waist, the other to what Joseph said was a Model-T re-machined axel that served as an auger. The hole funneled to a narrow opening at the bottom. With a mighty contraction of his arm muscles, Gene threw the pipe right through the hole. And he came tumbling after.

If the hole had been any wider, I would have been on the bottom of the lake. So here I am embarrassed beyond words that I just muffed up big time in front of these two elderly men. Thank goodness, they didn’t laugh at me. To this day, I thank them in my mind.

Dripping with water up to his elbow, Gene chiseled a second hole. He heated a coffee can of water on the stove, then poured it down the hole to keep the ice open. In the meantime, Joseph and Otto were laughing and playing and singing.

Yes, there was a little imbibing going on. But they never acted drunk. Later they told me it was cognac and schnapps. They were telling tales and just having a good time.

In the middle of the storytelling, Gene leaned against the wall in the corner near the stove and fell asleep. Then suddenly, Gene woke up—not because the older men were noisy, but because they were silent.

I heard my grandfather speaking in a language I’d never heard, which turned out to be French. He was naming the different communities in France during WWI . . The name of the community was the name of the trench. My grandfather was a truck driver, loading ammunition and carrying it to the different trenches. Well, he got done in the language I didn’t understand, and it was silent. Silent. For a long time. . .

Then all of a sudden, Otto sits straight up and says, “Joe, let me tell you what I did in World War I. I was a sniper for the Kaiser, and my job was to shoot ammunition deliveries to the trenches. Silence, silence, silence. Neither one of them moved. They were flickering in the lantern light.

Gene tried to figure out the implications of this revelation. Then Otto sat up even straighter and looked at Joe and said, “Joe, I’m so thankful that I didn’t kill you.” More silence for a seeming eternity. Gene kept trying to figure out what was happening. Then all of a sudden, the two older men started laughing again, drinking more cognac and schnapps. And not another word was said about it.

And I’m going, how is this possible that these two guys can be together for fifteen or twenty years, and neither one knew what the other one did in the war. . . Even though I was just seven years old, I would never forget that.

And Gene didn’t. Years later, his draft number was 11 in the lottery during the Vietnam War. But he was haunted by the story he heard as a seven year-old in the ice fishing shack. He couldn’t imagine himself picking up a gun and killing someone else, especially someone who might turn out to be his fishing buddy. He didn’t belong to a peace church, so he and his wife made plans to go to Canada. Gene turned out to be 4F with heart damage, so he remained in the U.S. But he always imagined what he might do if he were forced into battle.

Anyway, I thank my grandfather for drinking cognac and telling that story that night.

After his ice fishing experience, Gene Zdrazil navigated through the rest of his life by the stars.

Listen to Gene and others tell their stories on my Buggy Land podcast (Episode #43):

Dr. Eugene Zdrazil is the owner of the River Junction Chiropractor Clinic near Lone Tree, IA.

Please read and support my colleagues in the Iowa Writers Collaborative:

Thank Gene and thank you for sharing this unforgettable story.

My husband is an ice fisherman and I firmly believe this activity is a bonding ritual. Sure, a source of food. But time alone or with friends can be powerful. Thanks for sharing.