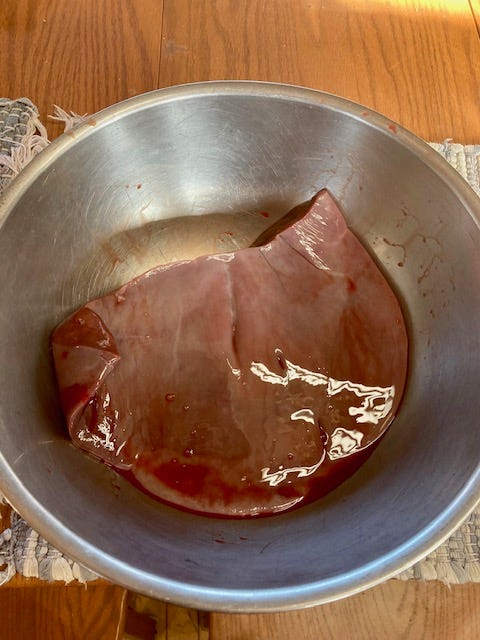

It started with a hunk of beef liver. I’d stopped by my Amish neighbors—Eli and Naomi’s Yutzy’s farm—to pay a bill I owed them. We stood in their breezeway, filled with old chore clothes, jackets, caps, overalls and five-gallon plastic buckets. The Yutzys had begun their butchering for the season, a task that doesn’t start until the weather turns cool (no flies) but not too frigid (no frostbite).

“Do you like liver?” Eli asked.

“Love it,” I said.

“Would you like some? We butchered a steer this afternoon.”

“Can you spare it?”

“We have more than we’ll ever eat.”

Eli pried the lid off one of the buckets filled to the brim with shiny dark brown liver. He snapped open his pocket knife and sliced off a huge chuck, dropping it into a plastic bag.

“What do I owe you?”

Eli shook his head.

I asked if he was going to butcher hogs, too. I like beef liver, but I make pork liver into braunschweiger.

Eli gave me a quizzical look.

“It’s like your liverwurst,” I said.

“We’ll be butchering three hogs next Tuesday. Come back then and we’ll have pork liver for you.”

Next stop: the Amish Grocery Store. There, I found a whole display of butchering supplies: hooks, knives, casings, trussing twine, paper, and spices crowded the shelves. What English grocery store carries these things? I picked out my spices and casings and could almost taste my braunschweiger. Few of my English friends like organ meat and turn up their noses at it. For me, it’s like Proust’s madeleine.

I remember standing in the butcher shop on Main Street in Manning, Iowa, where I grew up, the case filled with steaks and chops, hamburger and baloney. Gus, the butcher, stood behind the counter with a white cap cocked on his head and a broad grin on his face.

“Can I have a hot dog?” I asked.

“Can I have a hot dog, please?” my mother corrected.

Gus smiled and pulled out a plump hot dog from his case, handing it to me on a piece of wax paper.

I gobbled it up—raw—before my mother could even place her order.

Home, I sat in my chair at the kitchen table, watching the neighbor’s bird and squirrel feeder out the window. I delighted in the colors, shapes and sizes of the birds, the bright red male cardinals with their black chin patches and masks around their eyes, and the duller female cardinals, blending into the environment, safer for nest sitting. I slowly figured out that the bright male yellow summer goldfinches and duller females, both molt and turn a drab brown in the winter.

Little could pull me away from my ornithology until my mother unloaded her brown paper sack filled with groceries, took out the roll of braunschweiger she’d bought at the butcher’s, sliced off a hunk and spread it on a cracker. I could tell by the tiny quantity that my mother gave me that the sausage was either really expensive and she didn’t want to waste this precious food on me or she thought I was going to spit it out.

“Now this is really delicious,” she said, holding the cracker out to me. “Take a bite.”

The braunschweiger sat on my tongue. Just as I had taken in all the species, sizes and colors of the birds, I took in the taste of this new meat. Too young and with too little experience to identify these flavors—the liver, pepper, onions, and mace—I ventured into them as a whole, as if my neighbor had just filled his feeder and the birds were flocking to it all at once on a snow-covered winter’s day. Mmmm, I thought. Not sure about this new taste, but with my mother’s recommendation, I chewed and let the concoction slide down my throat. Yes, I decided, yes, she was right!

So, braunschweiger always brings back good childhood memories for me. My mother and I out shopping, the stop in the wondrous butcher shop with all the shapes and sizes of the contents in its case. This shop was similar to a business that my great-uncle Jim had once owned in town, undoubtably creating a flood of similar memories for my own mother. Her family had fled famines, poverty and political turmoil in Ireland to come to the United States. Native Irish speakers, first, they had to learn to speak English. Then they settled in Manning, Iowa, where they got a taste of braunschweiger and learned German in a town settled mostly by immigrants from Schleswig-Holstein.

Home in my chair and a kitchen filled with good smells, I glanced out the window, the birds alighting on the feeder. The offering of a new food on a cracker awakened my sense of taste, widened my palette, and strengthened a family and community bond—cultures coming together, molting, adapting to conditions. Such a simple act, a child eating a new food, a cracker with a liver spread. Such a complex action of the taste buds lighting up the gustatory cortex of the brain, creating an indelible image.

A week later, I pulled into Eli and Naomi’s lane. Five Amish men dressed in black huddled around a fire, a large black kettle resting on a grate over an open flame. Eli stirred the contents of the kettle with a homemade paddle, leaning his weight into the action, steam and smoke rising into the nippy air.

“What do you have there?” I asked.

“Liverwurst,” Eli said.

“Am I too late for the pork liver?”

“No, we saved some for you. We don’t like liver in our liverwurst.”

“What goes into it then?”

“Pickings from the bones.”

A pile of bones, having been simmered in the kettle for broth, lay a few feet from the fire, Joe and Marlo, the farm dogs, chewing happily away on these leftovers. Next to the bones was a platter of cracklings, or pork rinds. Eli picked up a couple and placed them in my hand and I ate the tasty treats.

The men continued to stir the labbawurst, slowly adding the broth.

“Now try this,” Noah, one of the men at the kettle, said. He spooned out a small dish of the liverwurst that had the consistency of oatmeal and handed it to me.

Hot, mushy, and smokey, the delicious concoction was almost as good as braunschweiger.

An old tractor was parked right next to the basement window of the house. Two belts ran from the tractor through the basement to an industrial meat grinder. Inside, Naomi was stationed at the grinder with a five- gallon plastic bucket full of pork. Another woman was stuffing hunks of meat into canning jars. Another was washing down the counters with a disinfectant. Yet another woman was slicing meat with a cleaver, a sleeping baby strapped to her chest in a carrier.

Children, both male and female, were carrying canning jars to a large sink for a soak in sudsy water. At another table, school age children were cutting up one-inch cubes of fat for rendering. Another girl swept the floor, back and forth, back and forth, picking up any tiny particle of meat or dust that might land there. In a back room, I heard the rush of steam release from the valve of a pressure cooker.

Heads down, intent on their tasks, no one talked or visited. Instead, they moved along like a well-orchestrated symphony without a conductor, each person simply knowing his or her rehearsed part. They knew when to grind or chop, when to wipe or sweep, when to take a moment of rest before beginning the next movement of this performance.

Piles of baloney were stacked on one table, piles of summer sausage on another.

“How do you want your liver ground?” Naomi asked.

“Medium?” I guessed.

“Medium,” Naomi echoed. “Too small, and it will turn to mush.”

Naomi adjusted the grinder plate, then flicked on the machine. Brerumm, brerumm, Naomi guided the liver down the shaft, the blade making quick work of the pork, the meat smoothly and evenly falling out and into a small plastic bucket. Naomi fit a lid on the bucket and handed it to me.

“Have you everything you need?”

“Yes, I found the casing and spices at the grocery.”

I tried to pay Naomi and she just shook her head.

It was understood I would pay her back at another time with a ride to the doctor or the pick-up of some groceries at the store.

I climbed back in the car, knowing that the afternoon sun was moving toward the mid-point and the workers would soon pause for a few minutes to share some coffee and cinnamon rolls. Two families, both Eli and Naomi’s people would socialize together, catching up on the local gossip, the women and children on one side of the room, the men on the other.

The day would end with the fire put out and the basement cleaned so well that you would never know that anything had happened there. The grinder and butchering tables would be lifted into a wagon to travel down the gravel road in the morning to another family, this scenario playing out for about a month until all the farms in the neighborhood had completed the job.

Who else gets to see home butchering? I asked myself. And where were my friends on a day like this? Many of my English friends were in warm climates for the winter—Mexico or Arizona—playing tennis or jogging by the beach, trying to get exercise. They might pause in late afternoon for a cocktail, and if they eat meat at all, they might then sit down to a dinner of pork chops in a restaurant, then without a thought, lift their forks to their lips.

“Have you been bothered by coyotes?” Eli asked when my neighbor Donna and I had stopped by with Christmas presents.

“No, but there’s a pack of them living down by the creek. I hear them howling at night. Why, what happened?” I asked.

Eli said that when they had finished butchering, they’d left a 5-gallon bucket of organ meat outside near the house in the cold. Eli had secured a lid on the bucket, and that night he and Naomi fell into bed exhausted.

“In the middle of the night, I heard a thump-bump right outside our window. Then Joe started barking. What in the world? Thump-bump, the noise kept up, and Joe got more and more shrill.”

Eli began acting out the scene. He crouched down, pantomiming grabbing his rifle, then opening the window.

“I looked out, but didn’t see anything amiss. But Joe barking and snarling. He’s got something, I knew.”

Eli tried to remove the screen, his hands fiddling with the imaginary window. But he couldn’t see well enough in the dark, and it’s not like an Amish man can flick on a light. Eli grabbed his gun and crept around to the front door. He pantomimed quietly turning the door knob, and tiptoeing out onto the porch. He wasn’t sure what he was going to encounter.

“There was the coyote, prying the lid off of the bucket. The thump was him lifting the lid. The bump was the lid refusing to release and falling back in place.”

Finally, Wile E. Coyote had the lid off and a hog heart in his mouth.

“I stepped toward him, but then he was off and running. I called Joe and went back into the house to sleep.”

“Did you get a good look at the coyote?” I asked. I was enjoying not only the drama of the story, but Eli’s dramatization—better than many professional stage productions I’ve seen.

“Just his outline and his shining eyes,” Eli said.

“What did his eyes look like?”

“Come on, Mary,” Donna said. She knew I would do anything for a good story and we had thirteen more deliveries to make.

I climbed back into my car, thinking about Eli’s hogs, my braunschweiger, and the coyote. I thought about my friends’ pork chops and our food system, how most of our meat is grown in very efficient CAFOs these days, or Confined Animal Feeding Operations. From cradle to slaughtering house grave, the whole system is controlled by Big Ag meat producers. Hogs are raised in small stalls inside large temperature-controlled buildings, never to have their hooves touch the ground, their feces dropping down into large manure pits, the pits regularly emptied with the contents spread on the farm fields for fertilizer. Neighbors complain of odor, air and water pollution.

The hogs don’t get to wallow in the mud or glean the cornfields. They aren’t fed table scraps. Instead, hundreds of hogs are kept in one place inside a usually windowless building. Food is brought to them with a diet of 62.1% corn and 13.6% soy with added nutrients and minerals. Animals packed in indoor buildings create perfect breeding places for viruses and bacteria that are then treated with antibiotics and other drugs.

At slaughtering time, hogs are loaded into semis and driven to nearby rural processing plants. There, they are butchered on an assembly line by low-paid workers, often immigrants who perform one specific motion hour after hour, day after day. Repetitive injuries are not uncommon. The hearts and livers of the hogs are usually saved, the rest of the offal used in by-products in everything from animal meat meal, to gelatin, to pharmaceuticals like insulin.

Those of us who eat meat need to seek out and buy products raised on family farms. Eli and Naomi’s farm is the antithesis of a factory. And home butchering is an endangered skill. It’s not always perfect, but there is so much to learn from a small family operation—from the bird feeder outside their kitchen window to the steam release button on the pressure canner. From the taste of braunschweiger to the taste of labbawurst.

There are certainly exceptions, but as a whole, free-range animals, raised outside of confinement, are healthier and fed more nutritiously. Farmers are more directly involved in their care and life cycle. Most of us don’t want to think about butchering. The difficult things in our modern world are hidden and out of sight. In hospitals and nursing homes, in slaughtering houses. There is so much to learn. Most of us live with smaller and smaller family and friend circles, unaware of where we might get a great cinnamon bun.

Slaughtering your own meat? Who does this anymore? Who has the know-how? Who takes the time? Who has a traveling grinder? Who has both a baby carrier and a cleaver? What are the indelible images it creates? And who has the courage to do battle with a coyote stealing your heart?

Listen to the podcast of Heart and Soul:

Please support my colleagues in the Iowa Writers Collaborative:

Iowa Writers’ Collaborative Columnists

Laura Belin: Iowa Politics with Laura Belin, Windsor Heights

Doug Burns: The Iowa Mercury, Carroll

Dave Busiek: Dave Busiek on Media, Des Moines

Art Cullen: Art Cullen’s Notebook, Storm Lake

Suzanna de Baca Dispatches from the Heartland, Huxley

Debra Engle: A Whole New World, Madison County

Julie Gammack: Julie Gammack’s Iowa Potluck, Des Moines and Okoboji

Joe Geha: Fern and Joe, Ames

Jody Gifford: Benign Inspiration, West Des Moines

Beth Hoffman: In the Dirt, Lovilla

Dana James: New Black Iowa, Des Moines

Pat Kinney: View from Cedar Valley, Waterloo

Fern Kupfer: Fern and Joe, Ames

Robert Leonard: Deep Midwest: Politics and Culture, Bussey

Tar Macias: Hola Iowa, Iowa

Kurt Meyer, Showing Up, St. Ansgar

Kyle Munson, Kyle Munson’s Main Street, Des Moines

Jane Nguyen, The Asian Iowan, West Des Moines

John Naughton: My Life, in Color, Des Moines

Chuck Offenburger: Iowa Boy Chuck Offenburger, Jefferson and Des Moines

Barry Piatt: Piatt on Politic Behind the Curtain, Washington, D.C.

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Buggy Land, Kalona

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Emerging Voices, Kalona

Cheryl Tevis: Unfinished Business, Boone County

Ed Tibbetts: Along the Mississippi, Davenport

Teresa Zilk: Talking Good, Des Moines

To receive a weekly roundup of all Iowa Writers’ Collaborative columnists, sign up here (free): ROUNDUP COLUMN

We are proud to have an alliance with Iowa Capital Dispatch.

Mary, that was a very good piece on the lost art of butchering! My roots are Ost Friesian German, and like you, where we came from you ate everything but the squeal of the pig! It was simply the business of survival for the people in the old country, and the extension of what you always did when you got here. So I grew up on "parts" brains, liver, heart, tongue, head cheese, ox tail, that sort of thing. I wasn't much for blood sausage, but that too was available. We were never as adept as the Czech folks at making something out of nothing I was later to find out, moving to Cedar Rapids in the 70's when "Czech town" still had two butcher shops that sold pig ears, pig tails and pig snouts! Back at home on the farm growing up we would ocassionally butcher a hog and the business of burchering chickens was often a family affair with everybody taking part. Kids picking chickens, Dad whacking off the heads, and my mom, aunts and my grandmother in the basement with meat scissors in hand, gutting and parting out chicken or singeing off the pin feathers, then wrapping them up in freezer paper and into the freezer! Amazing how quickly 50 or 60 chickens could be dispatched, cleaned and turned in Sunday dinner! I haven't even done chickens in over 40 years and since I quit hunting I haven't even cleaned a squirel or a rabbit in fifty years! Thanks for the memories! My German grandmother had a recipe for what she called "Stip" that would be something we would eat at this time of the year. When you butched a hog you had this thick fatty bacon and we would fry it down till it was relatively crisp and eat that, then we would add flour and black strap molasses to the drippings and make a gravy out of it, spread it on bread and eat that for those long cold walks to country school in the morning! Today, doctors would be charging my folks with "child abuse" for attempting to kill us with grease and coolestoral!

Mary, loved this. We have always had a tradition of eating fried liver and gravy for Christmas morning. This stemmed from long ago with my grandmother’s family slaughtering the day before Christmas to provide meat for the holidays. The organ meat was the first to spoil before refrigeration so they fried it up. For years it was a way to test boyfriends and girlfriends’ adventurousness and weed out the picky ones.