I let down the front wall of the bluebird house, the gateway to the inside of the box, and saw four eggs–three blue and one white–in the tiny nest woven from grasses. Oh, wow! The previous day there had been nothing but the nest. And now the female bluebird had slipped in without me noticing, and quickly and efficiently, laid her eggs.

We did it! Now we have bluebird eggs, I thought. I’d given up hope that this was going to happen. I’d found the brightly colored boxes at the Amish bird seminar last spring. Eighteen-year-old Joel Yoder stood at a booth in the side room. We broke for lunch and participants streamed by tables filled with bird books and feeders, binoculars and scopes. The bluebird boxes immediately caught my attention.

Painted orange, white, and blue with the head of a bluebird affixed to the top, the boxes were going to look great in my yard. I could imagine them taking up their spot, intermingled among my yard art: my menagerie of metal hummingbird and goat sculptures, my frog whirligig, and my four Amish-made bird feeders fashioned in the shape of a cardinal, bluejay, oriole, and goldfinch.

But I’d forgotten my checkbook, so I told Joel to reserve two boxes for me. I would stop and pick them up in a few days. And oh, please write down explicit directions for their installation. A few years ago, I’d bought a couple of cheap bluebird boxes and nailed them to fence posts under a tree in my pasture. English sparrows quickly occupied them and the boxes fell apart in one season.

Soon, but not as soon as I’d hoped, it was over the ridge and up Joel’s steep drive, bluebird boxes lining either side of the road. The Yoder’s small homestead was wedged between two deeply wooded ravines. At the top of the hill, two rough collies—one tri-colored and one sable—greeted me quietly with a curious gentleness. They guarded two pups in a pen attached to a large dog house.

The Eastern bluebird, a thrush and a relative of the robin, is a relatively small bird, bigger than a sparrow, but much smaller than a bluejay. Bluebirds may have two or three broods a summer with both parents caring for the offspring. Occasionally, the fledglings from a previous brood will help their parents care for their younger siblings.

The Eastern bluebird’s most common call is a soft, low-pitched tu-a-wee. Listen:

Bluebirds were in sharp decline in the twentieth century. They suffered from introduced species—sparrows and starlings—and loss of habitat, and the rising use of pesticides. Farmers began using metal rather than wooden fence posts that had once provided nesting cavities for the birds.

Then in the late twentieth century, conservation efforts helped bring back the bluebirds. More and more farmers installed boxes for nesting, and the birds became a protected species under the Protection of Birds Act (1975.) Bluebirds eat insects, up to 2,000 bugs per day. Grasshoppers, beetles, crickets, worms, snails and more are all bluebird delights. Traditionally, bluebirds have been farmers and gardeners’ friends, keeping pests under control.

Much folklore and sacred symbolism surround these birds. People from an array of beliefs believe bluebirds are a symbol of joy, hope, or good news. Others think that the birds are a connection between the living and the dead. Still others think that the birds are sent down from above to us to deliver important messages.

Joel came out of the door to the house, a ranch-style building with a very non-Amish, suburban look. For a second, I was confused. Did I have the right place? Then I realized that this property had most likely once been a hobby farm whose owner had gotten tired of the long commute to the city. The Amish had bought it, ripped out the electricity, built the barn, and moved in.

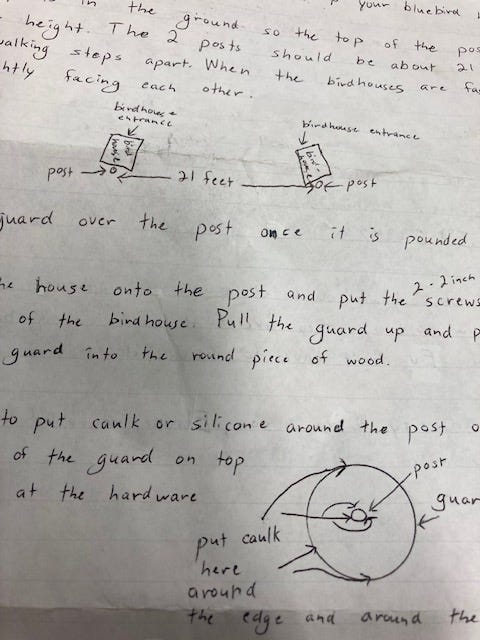

Joel loaded the boxes, poles, guards and hardware into my car and handed me two sheets of paper with tiny handwriting entitled Instructions on How to Put Up your Bluebird House. His explicit directions included tiny drawings of the boxes spaced 21 feet apart and slightly facing each other.

He also advised caulking around the post and the around the edges of the guard.

Put caulk here he suggested, including another hand-drawn picture of the guard. Then he let me know me. Caulk can be purchased at the hardware store.

Joel instructed me to put some sawdust in the bottom of the cup to stimulate bluebird nest building. He told me how to prevent English sparrows from occupying my boxes, and offered his help in identifying bird nests. (I could call his phone shack and leave a message with the description.) English sparrows, an invasive species, not only invade bluebird boxes, but they also storm occupied boxes, killing adults and nestlings.

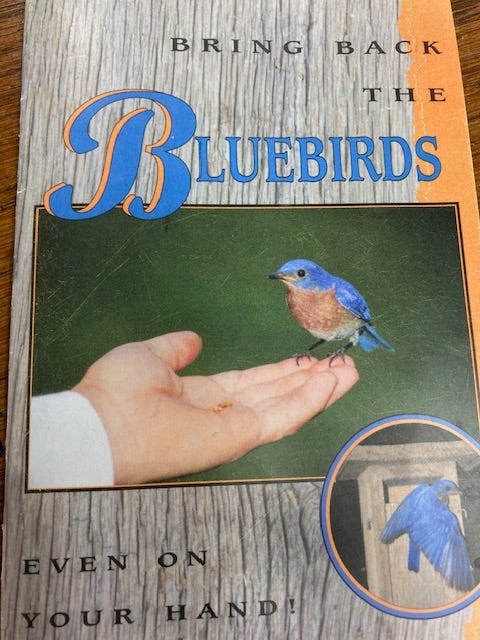

Then Joel suggested I buy the book Bring Back the Bluebirds, Even on Your Hand, written by an Amish man who had grown up as a boy loving the species. He’d found a tender way to approach the birds with their favorite food (meal worms), and eventually had the birds perching on his hand.

Joel gave me the name and address of a fellow bird lover who sold the book out of his shop.

If you want, you could tell Ethan or whoever is the cashier that Joel Yoder told you they have that book. You don’t have to if you don’t want to. For your curiosity, Ethan’s son, Eli, married my mom’s sister, so Eli is my uncle.

Home with my book in hand, I installed the bluebird boxes in my yard, near my garden where I could watch them from my porch.

“Put up the boxes where you can enjoy the birds!” Ethan had told me. “Just not in tall grass.”

So, I pounded in the post according to Joel’s diagram, pacing off the feet between the boxes. I slipped the boxes over the pole and caulked around the guards, then stepped back to admire my work.

An explosion of birds swirled around me: barn swallows, finches, sparrows, kingbirds, and purple martins twilled and called, dipping and diving toward the boxes, circling my head, landing on the garden fence, landing on the top of the boxes. I sat on the porch and watched this celebration, thinking that I’d certainly gained approval from the neighborhood winged kingdom.

Except for the bluebirds, those more reclusive creatures who don’t enter into the boisterous feast at the feeder. Where were the bluebirds? Would they eventually come? I waited for days before I saw them. Then more days before I discovered the eggs in the box.

I watched the birds scoop up insects from my garden, thanking them for their presence. They were indeed bringing me joy. And what connection would they make between the living and the dead? What important message would they bring?

All paid subscriptions are donations to AgArts, a non-profit that imagines and promotes healthy food systems through the arts.

I am pleased to be a member of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. Please join us on Sundays for our Round-Up. Sample, support, and subscribe to our individual writers. Read for free or as a paid subscriber.

Mary, pray tell, what were the birds whenthe eggs hatched and why one white egg? I do miss Bluebirds. See an occassional one in Maine nd did see a beauty in Colirado Springs in April. No cardinals in CO.

Mary, when you let down the front wall to see inside, were you worried that you might be disturbing the nesting process? Just wondering. Also, is the front wall attached at the bottom, or does it lift off? Thank you for an enlightening post!