I walked by the realtor’s office in Clifden, Ireland. There in the window was a notice for a cottage for sale near Cleggan, right on the edge of the sea. This historic cottage, the ad said, was ready for some tender loving care and renovation. Huh. Maybe I could afford to buy and fix up a small house in Ireland. What fun would that be?

I pressed my head to the window glass. No picture of the cottage. Just a tiny map to the location. And an extraordinary price. One million euros. 1,000,000? Oh, this had to be a holiday home, a modern house built by vacationing Celtic Tiger Dubliners. No, the ad said historic. Maybe the price was a typo. Surely, they meant 100,000.

I found my way to the location and was stunned to find nothing but a ruin, a pile of tumble-down rocks forming the outline of an old cottage. Was this some kind of joke? It looked like there had once been a village of about 20 houses here. They were all in ruins with the harsh wind honing its sharp blade on the stones. A small sign nailed to a post announced: Rossadillisk.

“Fishing industry?” Paddy O’Halloran had said when I’d visited him months before. “Yes, there used to be quite a bit of fishing in this area. But most of it stopped with the Cleggan Disaster. It made ghost towns out of villages like Rossadillisk. After the disaster, men just never wanted to venture out to fish again.

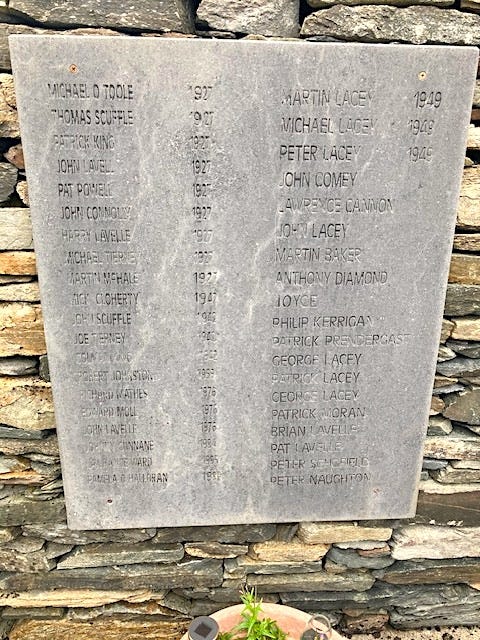

The Cleggan Disaster took place on the night of Friday, October 28, 1927. As was the custom, the men piled into their pucans, vessels slightly larger than the traditional currachs, light canoes made from tarred cow hide stretched over small wooden frames. The pucans usually carried five men pulling back oars to glide the boat through water, with seven nets to catch mackerel and herring. The men carried little bottles of holy water under the bow and rosaries in their pockets.

At about 5:00 P.M., the weather calm, a light rain falling in a gentle wind, four boats carrying 20 men, shot out from Rossadillisk. Five more boats with 23 men departed from the East End of Inishbofin. More boats left from villages in neighboring County Mayo. About an hour later, the fishermen let down their nets, nets that they had spent the long, dark days of the winter making and mending.

In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Amen. They sprinkled the holy water on their nets. They knew that they were at the mercy of God and of the sea.

Accidents and drownings were a fairly common thing here on the rough waters of the Connemara shore. But none of the men knew how to swim. They thought it better to just go down without a struggle, abandoning themselves to their fates.

Yet the community didn’t wallow in the danger before them. A tight knit community, the people of Rossadillisk and Inishbofin pulled together, helping each other out, repairing their neighbor’s thatch when it was blown off in a gale. Sometimes, they rowed across the bay to visit each other on Sundays, or even spend the night. In the evening, they shared what they had—brown bread and fish, storytelling and singing, playing cards and dancing. Good craic, good fun. A céilí set dance had been scheduled in a hall in Cleggan later that October evening in 1927.

In Cleggan, a woman had tried to warn the fishermen about a coming storm. She’d walked the seven miles to Clifden that morning where she had heard the news. But by the time she’d walked back home, as fast as her bare feet could carry her, the boats had already departed.

At about 6:00 p.m., a retired physician, was listening to the weather forecast on a magnetic radio, attached by wires to two poles outside his little cottage at Cleggan Farm. Dr. Holberton heard the storm warning and immediately sent his farmhand racing down the road on his white horse to Rossadillisk. But he, too, was too late.

In view of their family cottages on shore, the boats were already out in the bay with the great waves crashing down upon them, tossing the fishermen up into the air and down upon the rocks. A fierce wind blew up suddenly, ripping the roofs off of sheds, blowing out the candles, and tossing the newly harvested hay in all directions.

People were left in their cottages in darkness, weeping and wailing for their breadwinners. If a man didn’t have a wife and seven children, he had elderly parents or siblings to support. Parishioners at Our Lady Star of the Sea Church in Claddaghduff, huddled together praying the rosary, their faces ashen, the slates flying off the roof above them.

Below, the land was divided by stone walls and hedge rows into small plots, not more than 2 acres. Here, the family eked out a few fields of potatoes in lazy rows made of composting seaweeds spread across the rocks. For income and nourishment, the families turned to the sea. Sometimes the fishing was abundant, sometimes scarce, depending largely upon the restraint of the fishermen themselves.

But it was hard not to keep fishing. This was one of the poorest parts of Ireland with lots of rocks and very little soil to grow food. The men risked their lives to save their families from starvation.

“This land,” the local archeologist had once told me as we came upon my family homestead in Claddaghduff, “is the worst land in the township, which is the worst land in all of Connemara.”

Once night had fallen upon the land, families began searching the shore for their loved ones. One man came upon an arm sticking up out of the sand. He rushed to pull what looked like his son from the muck, only to hear the screams of a neighbor, his own son lost to the sea. Night sank into complete darkness, the beach lit up with the lanterns of mothers hunting and hoping.

By daybreak, five men had been found, placed in coffins, and carried to the church where Father O’Malley received the bodies and said a high Mass for the departed. They were carried over to Omey Island and buried in a mass grave.

The days progressed. Another man was found washed up on the Cleggan beach, another near Letterfrack, another washed up north by Achill Island. Altogether 45 men were lost. The men were placed in coffins in the town hall where the celi dance had been scheduled to be held, awaiting the coroner. Small candles flickered in the eery darkness.

Patrick Concannon became a folk hero. For seven hours his boat and crew spun around and around the surface of the sea. Sleet and spray blinded the men, but Patrick, always in the bow of his currach, shouted words of encouragement, pulling back hard on his oars.

At 3:00 a.m., the men were finally hurled ashore. They lay on the beach battered and exhausted, their clothes in tatters. By Saturday afternoon they made their way back to Cleggan, then they were towed to Inishbofin where their families were overjoyed to see them. His eyes damaged, Patrick had to be led about, his hands swollen three times their size, frozen into the shape of his grip on the oars.

A reporter for the Irish Independent visited Rossadillisk on Saturday evening. He saw one woman whose brother, her only support, was lost.

She was alone, all alone in the world. How she cried and wailed to the heart bruised young priest; how she clung to him and prayed to the good God to send another storm, that the sea would bring back her dead.

A collection was taken up for the widows and children of the lost fishermen. But the survivors of the disaster never received enough money to literally keep them from the poor house. Ultimately, they all left the village. Many emigrated. Some were taken in by relatives. Others died early deaths in a place where the motto was Fish or starve.

In Rossadillisk that afternoon, I stood in the rubble of these people’s lives, and crossed myself. In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen. I mourned the men who were lost and their families who were forced to fend for themselves in a harsh world. I mourned these people who, living through years and years of poverty, oppression, and near starvation, still had the desire to pull together and help each other. And they still knew how to celebrate, entertain each other with stories and song. After risking their lives fishing in turbulent waters, they looked forward to getting together for a dance in the town hall.

No, one million euros wasn’t a high enough price for this cottage in ruins in Rossadillisk.

Want to support Buggy Land? Become a paid subscriber, or donate any amount to AgArts, a non-profit:

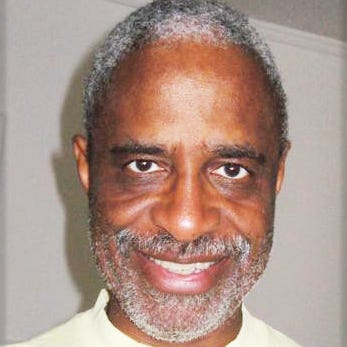

I am thrilled to be a member of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. Read and support my colleagues in this group. We include such luminaries as the fabulous writer and musician Dartanyan Brown.

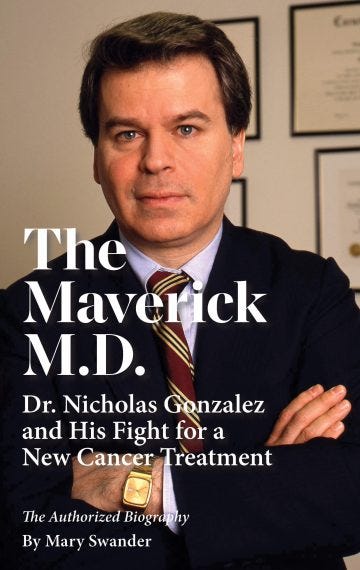

Want to buy my latest book? The Maverick M.D. The story of a brave Ivy League physician who created a nutritional treatment for cancer and upset the whole medical establishment. The book reads like a thriller but informs you of a new way to look at your health.

This is such a powerful story, Mary. Thank you for taking us along with you. I could imagine all of the horror and devastating sorrow on that shoreline. You are right, no amount of money will ever erase the misery. It is Ireland.

Thanks for this beautiful and timeless story, Mary! Tragic yes, and also a testament to the power of community and the obvious need for science in this world. If only those who needed to read such pieces could be moved to do so, and act.