Today I bought my own tombstone.

No, I’m not ill. I haven’t felt better in years, but recently I updated my will, and my lawyer suggested that I get my end-of-life affairs in order. She referred me to a local funeral home.

“Now, do you have a cemetery plot?” the funeral director asked, going down a checklist he had had me download.

“Well, sort of,” I said.

“How do you sort of have a cemetery plot?” he said.

I explained that my mother’s family homesteaded in western Iowa. They experienced the first white settler death in the area, so they sectioned off part of their farm, had a priest bless it, and from then on, the strip of land became “The Sacred Heart Catholic Cemetery.”

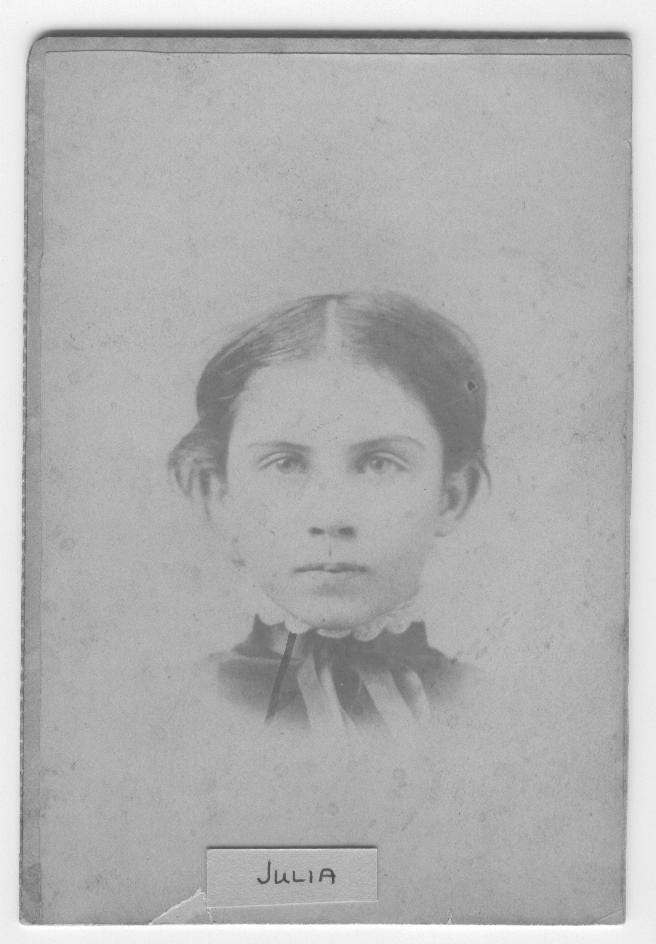

My great aunt Julia, who died in her youth, occupied the first plot, her grave marked with a small, plain, white stone with only her first name engraved on the top. A larger white granite family headstone rose up out of the flatland, assuming center stage. The names and birth and death dates of my great-grandparents and Julia are engraved on the family stone, then the markers of their nine other children filled in the surrounding spaces.

In childhood, I walked that land with my grandmother, over and over again. We put flowers on our relatives’ graves on Memorial Day. We stopped, crossed ourselves, and knelt down in prayer at the family gravestones. My grandmother named each of the relatives. “Here’s my brother Jim. And here’s Bob,” she said, confusing me, the stone reading Fred. “He loved birds and knew their calls, so we called Fred bobwhite, then just Bob.

“And here’s where I will eventually be,” my grandmother indicated the tombstone LYNCH and the space next to my grandfather who was the latest addition to the cemetery. And there’s enough room here for anyone else who would like a plot.”

My mother was eventually buried next to her parents, and my brother found his final resting place a few paces down the line, closer to the railroad cut with its few remnants of original tallgrass prairie, the bright blue clear horizon stretching for miles above him.

“Well, I think I’ve got a plot between my mother and brother,” I told the funeral director.

“But you don’t know?”

When my mother died, I had gone to the priest to secure my mother’s plot. He had pulled out a piece of paper, faded and yellowed, the corners eaten off by mice, the plots penciled in in a scramble of unintelligible markings.

“Hard to know who is where,” the priest muttered. “We’ll bury your mother next to her parents and hope for the best.”

The best didn’t happen. On the morning of my mother’s funeral, the gravedigger called me, just a couple of hours before the service. “Did you ever have another sibling?” he asked.

“No, just two brothers.”

“Maybe someone who died young?”

“No, that would be my Aunt Julia.”

“Someone more your age?”

“What’s happened?

Well, the digger had hit another coffin in my mother’s plot, an unmarked casket of a child. I didn’t know what to say, but an ingenious and practical Midwestern decision was finally made to dig a bigger hole, placing the unknown child’s coffin at my mother’s feet.

“Oh, there’s plenty of room for both of them,” the gravedigger said.

“There are lots of pioneer cemeteries just like that,” the funeral director finally said. “If you want to be buried there, the best thing you can do is buy your own tombstone, and stake your claim.”

I gave it some thought. Yes, I wanted to be buried in Sacred Heart Cemetery with the rest of my family. I’d lived in eastern Iowa most of my adult life in the middle of Buggy Land. I knew it would be more convenient to just be buried somewhere closer to my current home, but I didn’t have a family history here as I did with Sacred Heart. And I’d once written a book of poetry called Driving the Body Back about transporting my mother back home for burial. The long, dramatic poem had seen some success. It seemed only right to complete the tale with my own journey.

Years ago, I’d had another idea. Many times in the past, I’d traveled to Ireland, searching and finally finding my mother’s family farm and cemetery in Connemara. The Lynches were buried on Omey Island, a sacred site, a small western island, the only place in the whole country where the dead are taken out to sea for burial. St. Brendan’s graveyard was ancient, hallowed, filled with Celtic crosses, and family plots of clans with deep roots, and centuries of history with the place. You could stand on the Lynch plot and look out toward the strand, watching the waves part at high tide, and see the ruins of our tiny two-room cottage near the shore, squatting there on rocky, untillable soil, the gulls flying over another, treeless open horizon.

Ah, here it is, I said to myself. Here, I feel connected. I’ve found my real home. In the end, I will have my ashes strewn across the rocks here in St. Brendan’s. What a lovely ending to a good life.

But that lovely ending ended one evening in Sweeney’s pub. I’d walked there with my landlady’s dog Happy trotting alongside me, the usual mist of rain suddenly turning to a downpour, the wind blowing up into a gale. In Sweeney’s, I sat near the fire, a shivering, dripping mess. Two fishermen in slickers blew in through the door. They sat at the bar, water pooling under their stools.

“Did you get her done?” The bartender asked.

“Aye, he’s in,” one of the fishermen said, tipping back his pint of Guinness.

“But no more Yanks,” the other fisherman said.

“What can I do?” the bartender said. “The boxes of ashes just keep coming. In care of Sweeney’s Pub, the parcels say.”

“Tell them we’re full up over here.”

“Or at least, no more elaborate instructions.”

“What did this one want?” the bartender said. “I noticed there was a note in the box.”

“Jaysus, this one wanted us to row out in the currach, then circle the bay, dropping bits of ashes as we went, praying the rosary the whole time.”

“Did you make it out there all right?” the bartender asked.

“We did,” the fisherman said. “And Hail Mary, full of grace, just as we were about to sprinkle the ashes in the ocean, that swell came up.”

“Sure, it did.”

“Forget sprinkling the Yank,” I said. “Hold onto your oar, or you and I are bound for St. Brendan’s ourselves.

“I pounded the lid back on the box. Holy Mary, Mother of God, I just fecked the Yank in, one big lump, sinking to the bottom of the sea.”

After that, I rethought my burial plans. I began to realize that the concept of home is transitory. Major forces, whether political, economic, religious or agricultural, push people to distant lands where they, in turn, push others out of their homes. At any given time, we are suspended in space. We only know a fraction of our clan. We can have an emotional connection with those who have come before us, but we can’t really go back. One way or another, most of us live in a state of displacement.

So, I intend to have my stone installed on what I think is my plot in the Sacred Heart Cemetery in Carroll County, Iowa, and hope for the best.

I’ve also left some simple instructions. At the graveside, please read the ending of Driving the Body Back, then everyone can go and have a pint on me:

. . .And when Frankie asks about

the cemetery plot, I see my mother

going under, hear the clouds

break loose, the rain pelt down.

You stand with me again under

the canopy in your plastic

bonnet drawn tight under the chin.

We watch the incense circle

up into the sky, wait for

the priest, the acolytes,

all the other mourners to leave,

and say one last prayer together.

Then we tramp down the row,

you bending to pull some weeds

grown up around Jim’s stone,

vowing to do a rubbing of Julia’s,

her dates so dim. When we reach

the end where the land drops off

into the railroad cut, mud sliding down,

raspberries tangling up, our eyes

measure the space and you say

there’s enough room at least

for you and me.

Please support my colleagues in the Iowa Writers Collaborative: